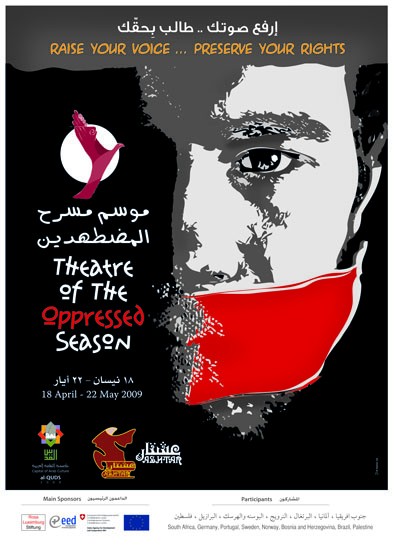

Theatre of the Oppressed Festival: Palestine, Apil 2009

World University Services of Canada, symposium, February 2009

THEATRE OF THE OPPRESSED FESTIVAL: PALESTINE, APRIL 2009

How did this all come about?

The Festival organizers sent out emails to various people . . . a network of people who have trained and who work in Theatre of the Oppressed! I have done work with a woman called Yolisa Dalamba who I have known for almost twenty years in many different capacities and she got a series of emails about the Theatre of the Oppressed Festival in Palestine, and she passed it along to me as something we could work on together. She trained with Boal in Johannesburg when she was teaching at Wits University in the 1990s. I had done Theatre of the Oppressed in the late 1970s and early 1980s . . . in the days when I went to the Space Theatre (as it was then called) and also at Community Arts Project in Woodstock. I continued some of this kind of work over the years and also began to incorporate it in my anti-oppression and anti-racism workshops with university students, women’s organizations and social justice organizations in Canada . . . so to cut a long story short, it was the Forum aspect of the Theatre of the Oppressed festival that got her thinking that perhaps I would be the best person for this particular challenge. There is a community of Black Consciousness and Afrocentric scholars, writers and artists, mainly South Africans, in Toronto and other parts of Canada with whom I have done all sorts of work, and we tend to do collaborative work and also share resources.

Almost all of the cast members are UWC students. You were a student there once yourself. Tell us why these particular students at UWC?

Both Yolisa and I are South African and we work with South Africans in Canada and people who use the expression of African descent. She had heard me speak about the students at UWC, after I watched the p-word in 2007, and also after I saw a few performances at the centre for the Performing Arts where I saw very strong performances by some of the male actors.

So you knew all of them before you cast them?

I only knew Melvin and Xolani from UWC—I had spoken with them previously when I taught there for a semester in 2007 and I got to know them that year. Zahra, the 14 year old actor is a student at St. George’s grammar and I had seen her perform and was really taken by her. She is also of a different generation . . . born in 1994 . . . one of Freedom’s children, and brought a unique vision and sensibility to the group. I was taken by her performance in a similar way that I was taken by Melvin and Xolani—so I contacted them. I had seen Wahseema and AJ in the p-word and really loved their performance—so I contacted them. I enjoyed watching them and observing what they brought to the stage. Wilton I met at our first rehearsal, which was really an Improvisation session, and I really loved his spontaneity, from day one . . . how he could get into character and go into Invisible Theatre without having to be told when or how.

Did you know ahead of time that it would work? I mean, how can you be so sure to choose people without the long selection and elimination process that goes with all Theatre work, and which actors dread?

I saw their performances, all of them except for Wilton, prior to contacting them for this particular festival. I had chosen a theme, the history of oppression in South Africa, as is customary with a festival of this kind, and I saw the scenes playing out in front of me with each of them playing very different roles. Every one of the actors has strengths that one recognizes if you’re a writer and a director and you know from your gut what will work . . . and perhaps from experience. They are all very different people, with different levels of energy, which come alive when they are exposed to particular situations and it was really a matter of making sure that we got deeper into those situations in our improvisation sessions and in our workshops . . . which is what happened. Then there was the part where I saw them work together, and they all worked very well together.

But this was not a scripted play. How did you manage to get the actors to get the work done without being scripted? I mean, what do they go by? What about cues?

I don’t think one can teach young people in South Africa about oppression . . . they experience it on a daily basis . . . and I mean this in the full range of experiences, whether as observer, recipient, agent, target. So, whilst the theme was the history of oppression, I wanted the theme to come to life as they workshopped situations. I was also very much aware, given the age-range of the actors, that they may not have had first-hand experience of certain aspects of the history of oppression and that (presumably) their parents may have told them about their experience growing up during the 1970s and 1980s . . . there are still situations like forced removals, xenophobia, etc. that they are very much aware of and this was evident when we went into improvisation. It was a question of acting alongside them in Improvisation sessions . . . where I played the oppressor, provoking them, challenging them to challenge me . . . to see how and where we could go. I knew that there was no way that I would want them to learn lines even though there were brief skits written . . . so it was really a question of capturing their spontaneity, seeing how they react to certain situations that we workshopped or that emerged out of improvisation . . . and noting those moments, making sure that those moments would be included in our skits.

What about styles, differences, surely it cannot be that simple?

Hmmm, I am not sure what you mean, exactly. I know for one, my style of warm-up is different to what I saw most of them do . . . often lead by the Wahseema and AJ who had previous experience with Boal and Theatre of the Oppressed. In Street Theatre, Guerilla Theatre, Protest Theatre, Method Acting . . . the method of warm-up is more vigorous—and I am more familiar with that style . . . it is psychic, physical, combative, sometimes even considered aggressive. I participated in some of the warm-up sessions they initiated, and was quite hopeless at some of them . . . which is fine . . . as I saw no reason why they should do warm-ups my way . . . because what they did suited their needs and they were the actors on the stage. There were times when I worked with some of them alone, like with Zahra for example, and I could do warm-ups differently, especially in the beginning as I was trying to establish how she would work with actors twice her age or 10 years her senior and she took to them very well as she played an oppressor in quite a number of skits . . . at the tender age of 14! Every actor, writer, director, has different styles . . . it should not stand in the way of doing productive work.

The festival was in Palestine—in the West Bank, is that correct? I mean you have to arrive in Tel Aviv, in that billion dollar airport and go through security and be interrogated and not tell them that you are going to Palestine, certainly not to the West Bank . . . in fact not even use the word Palestine . . . that is certainly what I have heard from friends and colleagues. What was it like arriving in Tel Aviv knowing that you will be taking part in a Theatre of the Oppressed Festival?

Mmm, it was tough, but I had braced myself for the situation. Good heavens, I grew up in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s . . . one learns how to deal with policemen, agents of a regime, with or without guns, and one learns not to be afraid of them . . . to treat them like instruments because that is what they are . . . not to give them any more power by even treating them like humans . . . not to speak to them as though they matter.

They held one of our actors back at the airport, on the basis that her Muslim sounding name urged them to question her about her motives for being there. I say “Muslim sounding name” because there was nothing on her passport that said that she was Muslim. In fact when we left Tel Aviv airport, upon our return, they asked many of the actors the derivation of their names. To come back to that situation . . . here were seven of us traveling together and I also had to check on our luggage, knowing full well that if all of us waited with her our luggage would be unclaimed and could be destroyed or sent back. So, I went off to collect it with three of the actors, and three of our luggage bags had been kept back. They stayed in two groups of three, while I went to find the people form Ashtar, as they had been waiting for quite some time and was very shocked when I walked into that billion dollar airport.

How long did they keep her?

Around 2 hours . . .

What did they do during that time?

At first she was told to wait until they were ready to see her—a tactic, clearly, to keep the person anxious, especially after being on two flights, tired, worn out.

They then asked her to open her email and her facebook account.

Was she okay afterwards?

I think so. As okay as one can be if you are 23 and was 8 years old in 1994 when Nelson Mandela became the first democratically elected President of your country. Her generation missed the fights with the police, the interrogation, and the fierce one-on-one combat that my generation was engaged in. She is also quite a gentle soul . . . and I would say that she handled it very well. Yes, she was upset, but overall she survived it and two of the actors with whom she is good friends stayed with her during that time.

And then? You meet the people from Ashtar and cross the Highway, the famous highway, known as Route 66, the apartheid highway as it is known, in the middle of the Holy Land. What did it feel like . . . did it look strange?

I knew what to expect so it did not look that strange. There was the portion of the road as we crossed over into the West Bank that reminded me of South Africa during the late 1970s with barbed wire and metal reminiscent of steel people . . . so there was a sense of familiarity . . . then there were boxed structures and demolitions, like the Bloemhof Flats, and District Six in the early 1970s and other parts of South Africa in the late 1970s . . . the smell of oppression, the land littered with reminders of an occupation . . . of a regime at work undermining the people whose land they usurp.

Did you travel all over Palestine?

We traveled in the West Bank. We performed in 6 cities in the West Bank and traveled to each of them every day as we were stationed in Ramallah.

In which cities where were your performances? Did you perform at Theatres only?

We performed in Jerusalem, Hebron, Tel Karem, Ramallah, Bir Zeit, Jenin and Nablus. We performed at various locations, sometimes at Universities, Children Centres, etc, where there was a theatre and/or where the city had its central cultural centre.

How did the public, or should I saw the spect-actors, respond?

The audience/spect-actors in Palestine were very engaging. There were members of youth groups, cultural groups, women’s organisations, the general public who saw the festival advertised, students, professors, workers, artists and writers, all of whom came to packed performances.

Here is a photo of the full run of one segment depicting mine workers in a conflict situation with management. The mine workers were forced to work for very low wages and with no benefits, not even the minimum. At this particular moment one worker is pleading with management on behalf of another worker, whose ill health has escalated. The two workers among them carry on, half-heartedly.

Here the spect-actors decide to join the workers, asserting that they will join the workers in fighting for higher wages and better working conditions. Management then instructs the spect-actors to work just as hard to see whether the workers are justified in their demands. With the additional workers (from the audience), the workers called for a strike and management eventually gave in to the demands of the workers.

In there any city which where you though the spect-actors responded better?

I can’t really I can say that each city had it uniqueness. In Jenin for example, we performed in the Freedom Theatre and the residents warned us about Israeli solders keeping a close eye. Nablus was the last city we performed in—we spent a few hours in the city, learning about its history, about its people, and we learnt a great deal from the spectactors that night, I think.

Is there any one city you liked best?

No, not really. Each city brings with it its own history . . . sometimes in quite horrific ways, but always in ways that are informative and interesting . . . this is the Holy Land that we’re talking about. Whether you are Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, an Aestheist . . . everywhere in Palestine one is reminded of the history of religion . . . and many cities are just breathtaking, just physically beautiful . . . in others I felt torn between loving the beauty, struggling to get it out of my mind as the guns of the Israeli soldiers were always present . . . everywhere. In Hebron, for example, within a small radius of land, there are more than 100 checkpoints, several just within 100 meters of the mosque . . . so whether you like it or not, the plight of Palestinian people is at the forefront of one’s thoughts . . . these situations were not explained to us, we experienced them. We saw the garbage being thrown from above, from Jewish settlements created by the Israeli State onto Palestinians who lived below in overcrowded, guarded environments, with barbed wire . . . and yet, the children were joyful, loving, full of life and many of them ran after us . . . one little girl kissed my hand, and just two meters away stood four Israeli soldiers with guns pointed everywhere they could find a little spot of dignity to aim their hatred at.

You are making my skin stand up. I didn’t think it would be that bad. What about Jerusalem? I’ve heard people say that one has not lived if you have not been to Jerusalem. What did it feel like to be in Jerusalem?

We went to Jerusalem on our first day of performance but really got to go back on the Tuesday, when we did not have a performance, and did a proper tour of the city with one of the actors from the Ashtar Theatre Company.

It felt strange, intense, mind blowing, on edge, a rush of nervous energy . . . the sensation of life and death, beginnings, origins, the birth of Christianity, the birth of Islam, and the birth of Judaism. The main Mosque there was just so beautiful. Only two of the actors went inside the mosque. I could not speak to anyone around me for a while as so many thoughts rushed to my mind. We took the path where Jesus was crucified and took the route of the pilgrimage, and also saw the site of resurrection, and walked along, with hundreds of others . . . people were placing their hands on the stone all around where Jesus walked . . . I had my quiet moments with the person with whom I was walking as I felt that words seemed unnecessary. People around us were crying, holding onto one another. We visited several of the synagogues, the main one and the Ethiopian one too . . . it almost felt too much, if you can imagine what “too much” feels like . . . like you are having an out of body experience, looking on, watching yourself walk through the Holy Land, as though you were watching a film in some way . . .

Actually, I had a weird experience as I sat in the van. When we entered Jerusalem I took a photo of one of the intersections as I remembered it from three days prior. It was an intersection that is the most popular, I was told by one of our drivers . . . and anyone who knows me will tell you that they do not regard me as being good with a camera taking photos as I prefer filming. And as always, quite by accident (which is really how I get a good shot or an interesting one) I photographed two young men, two Hasidic Jewish men, crossing the road without intending to, and at the same time the poster of the Theatre of the Oppressed festival was reflected in the mirror and it is reflected in the photo. Now you might wonder how one can photograph two people without intending to . . . but the colour of the clothes the two men were wearing blended in well with the surrounding colour of the buildings . . . a creamish pink, which is the colour of most buildings, thus allowing them to blend in. I had read about Hasidic Jewish people, that they are calledHasidim in Hebrew, meaning loving people, and many of their ideas come from the kabbalah. Their roots are in Eastern Europe, from the impoverished masses, and their clothes are meant to be simple, blending in with their environment, much like the principal adopted by Christian nuns, who started to wear black and white, as it presented the dress of the common people, allowing them to fit into their environment . . . The Hasidim also wear black hats, as black and white have always been the colours worn by religious sects and groupings . . . but that is another discussion . . .

Someone asked me how I managed to get that image in the photograph thinking that I must have used some clever “Director’s technique” . . . and I had to laugh and confess to her that it happened by accident.

Can you show me?

Sure.

And you didn’t plan this?

No.

What about the two men?

Sadly, I cannot take credit for that either.

This is an incredible photo. Tell me again how this happened?

I was leaning against the window and the poster was on the floor of the van and it was reflected in the window, which I did not know at the time. If you look carefully, you’ll see that the clothes of the two men almost blend into the surrounding area . . . one only sees their black hats and notices them by their hats.

I want to ask you so many questions, but let me ask briefly, if I can, whether the experience of being in Palestine changed your life or your view of the world and/or whether you think it did that for the young actors.

I don’t think it changed my life, I think it enhanced it. You cannot be there, travel around the West Bank, do Theatre of the Oppressed, be in Nablus and see where Israeli soldiers have shot into the walls with guns designed to carry bullets which are made of hundreds of nails, fired all at once, sprinkled over people who happen to be there, piercing them, killing them, scarring the walls, the physical environment, leaving their mark of death, leaving traces of humiliation everywhere for Palestinians to see, killing people by pulling them out of their homes, seeing posters of young men and women who have been shot . . . men and women who were not part of any movement . . . whose only real crime is that they are Palestinian. I cannot speak for the actors . . . I think most of them have indicated that they are still processing their visit, the experiences. Doing Theatre of the Oppressed in Palestine brought a certain kind of intensity to the work . . . our spectactors, people doing more than simply being audience members, were very involved, determined to challenge the acts of oppression that was being performed, and one does not always see that . . . nor do you experience people who are so willing and so determined to put a stop to oppression.

What’s next for you and for the group?

I am working towards taking some of the skits that we performed for the festival in Palestine to Canada and other parts of the world, if possible. I also work with a group of actors and writers in Canada, and we are doing a play on Steve Biko. Funding can be difficult but not impossible . . . so we’ll see.

*********************************************************************

WOMEN IN GOVERNANCE

Dr. Rozena Maart: Addressing gender from Cape Town to Canada.

Dr. Rozena Maart gives keynote address at World University Students of Canada conference

INTERVIEW AND PHOTOS BY HEATHER MACDONALD

GV CONTRIBUTOR

GUELPH, ON – As a native to Cape Town, South Africa, Dr. Rozena Maart witnessed various forms of oppression growing up, leading her and four other women to create the first black feminist organization in South Africa, Women Against Repression. She took that monumental step in her life and the lives of many South African women in 1986 and a year later was nominated as Woman of the Year. Maart moved on as a writer and won The Journey Prize: Best Short Fiction in Canada in 1992.

Currently living in Guelph, Maart was a sociology professor at the University of Guelph. She met and engaged with many students over the years, regarding their development trips overseas, often discussing how to better understand their own identity and their relation to the rest of the world.

On February 8, Maart delivered the opening keynote speech at the Gender Equality & Education Symposium hosted by WUSC Guelph. She took some time over lunch to talk to Governance Village about her personal accomplishments and the shifting world of gender equality.

Why did you choose to come here today and what is it that inspires the work that you do?

I think why I chose to come here today comes primarily from when I taught here a couple of years ago. I also live in Guelph and I’ve done a lot of workshops with the Guelph Resource Centre for Gender Empowerment and Diversity. It used to be called the Women’s Centre [but] people wanted to move away from the centre that was just for women and open it up for transgender people and all of that.

I’ve spoken at events at the university organized by different groups to talk more about some of the things that they felt were not covered in the curriculum but which they had felt they gained from my talk. In other words, when you’re going as a person doing development work, a lot of the students are learning about development in terms of the economic aspects, stuff around globalization and stuff around the social and political issues around transnationalism and leaving the [country] having theory but not understanding that they are going as an agent of their transnationalism and developing an awareness of how you should approach a community whether it’s rural or urban when you go to do development work. So for me it was about that.

I think for WUSC organizing this, it is important for them to highlight gender to recognize that the focus is not only the elimination of gender inequality but also to work with issues like what goes on in other countries when it comes to inequality, how to understand it, how to examine gender inequality, what it means. I think people’s own participation is all to kind of broaden the discussion because I think my knowledge and the experience I’ve had working with students not only in my profession as a professor in the past but also as somebody who lives here and does all kinds of work is that students have often said to me is that they’ve gone and they just did not know what to expect. So, I think it’s important that WUSC has put the Symposium on. I think it’s important that they continue to do the work that they do and I think it was important for me to be part of that and recognize that.

What was it that got you involved in the women’s movement or more specifically, gender inequality issues?

I think what happens is that when you grow up in a society where things are so divided in terms of what is racism and colonialism and somehow gender isn’t spoken about in that context, I think people from my generation, women from my generation, spoke out against those kinds of narrow minorities. Liberation should not be prioritized, this is first and that is second and gender was always seen as something that would happen afterwards.

So, myself included, in 1986, we started the first black feminist organization in Cape Town. We got a lot of hassles and a lot of flack from many people in the anti-apartheid movement. You don’t worry about stuff like that because at the time and still today, South Africa has among, if not, the highest rate of violence against women in the world so one of the things that I say is that we can lobby and we can fight for gender equality if it means that our voices are going to be heard in terms of changing legislation. There’s only so much one can do because one can legislate against anything but you cannot legislate attitude, y’know?

So it’s addressing gender inequality on all levels. It’s not just looking at it in terms of the disparity between what men do and what women do but it’s addressing it on all levels. Women Against Repression was started now almost 23 years ago and that work is still continuing in many different forms in many different organizations in South Africa, focusing on gender and transgender and sexuality issues and of course doing HIV and AIDS education but it’s also more widespread now and people don’t feel like they have to ask, “please, can we do this kind of activism,” it’s just a widespread, accepted thing that this is what happens in order for us to live in a society that’s more humane, that recognizes that women have the right to certain kinds of access.

You were speaking about how in 1986 you started the organization but then a year later, you were nominated for Woman of the Year. What does that mean to you?

I was 24; I was very young. It seems young now but at the time it didn’t feel like that. I think it was to me, more of a nomination for feminism and for black feminism because I think for women in national liberation movements around the world, where it’s always treated that if you demand something that the male leadership has not recognized as a demand, then you’re either being bourgeois or you’re taking on white-people-issues. Like, “oh that’s such a white thing, feminism” and it’s rubbish! I think for me it was like a vote for feminism that made it just the fact that we spoke of all kinds of things that the male leadership did not address in the anti-apartheid struggle for national liberation. Those men in those leadership positions did not make that an issue.

Looking back on everything that you’ve worked on, what would you say is your greatest achievement?

I think it’s the violence against women work. I think protest-politics still remains the most important because it’s a kind of education that shows people we should not be silent. I always say when people ask me what I like the most, I say I like to talk and write and think and imagine and put on performances through my writing, through drama about things that I’m not allowed to say. Why say things that you’re allowed to say? Because it’s the things that you’re not allowed to say that makes the most impact. We all come from communities where there are secrets whether the secret is sexual abuse or whether it’s racism and why keep the secret? Why not share it? Why not open it up? So I still today think protest-politics is one of the most important aspects of my life.

You talked a lot this morning about being aware of your identity and the people around you. You mentioned that you are “Christian by baptism, Muslim by culture and Hindu by heritage,” what does that mean for you and how does that play into your personal identity?

It plays into my identity in ways that, as I said, I consider myself black because I think history and experience gives you an identity. I think if you were born in England, you wouldn’t call yourself Canadian. I have a friend in Winnipeg, she was born in Nigeria, both her parents are English, she has a Nigerian passport and she said it was very hard for her to come here because she couldn’t say she was Nigerian to anybody because she felt it in terms of citizenship, not in terms of culture. She grew up with British culture and she had a Nigerian passport. She had never had a British passport in her life so I think experience allows us to call ourselves all kinds of things and especially when that experience forces us to.

When I was growing up, we didn’t have passports, our identity documents said “coloured” but it was only when I was 13 or 14 that I got to know of Steve Biko and what it meant to call oneself black. It was like an act of defiance to use the term and to take it on positively, not like a curse or an insult. Also, if we think black wasn’t just about the colour of the shoes or the colour of your skin, it was a way to sort of recognize that you had to fight through all of the other labels to use.

I think it’s like what people in the States have done or what queer people have done; they’ve taken the word “queer” to use it positively and for people like Steve Biko to say this is not just about skin, this is about your mind, this is about divide and conquer tactics. So what I meant by the [statement] was that I didn’t know my father when I was born, my mother and my father had split up so she lived in a Christian household. My grandmother was Hindu but I was baptized a Christian, my grandfather’s sister was Muslim. So, we had to have a halal house. Our neighbours were Muslims so I learned to cook next door. Also, the Cape Malay culture in Cape Town, it’s very, very present because the word “malay” is a Muslim word but Cape Malay comes from the Malaysians, people who brought Muslims from Malaysia during the times of rebellion in the 1700s and then brought into Cape Town and so that’s very strong, very prominent. It’s woven into the food, the culture, history. Then of course, my grandmother is Hindu but of course she was also converted and I think that’s part of my heritage.

I think that with the way Canadians are raised, you don’t have to classify yourself in any other way than to say, “I’m Canadian” so if you don’t have to then you don’t and sometimes through that process, people lose a sense of their history. They just don’t know because they’ve never had to think about it.

You mentioned that the UN is estimating a goal completely eliminating gender inequality by 2015. Do you think that it’s reasonable to put a number on that or do you think it’s possible to reach that goal?

Well, I don’t think anything is impossible. I think that part of what you see in history is that people thought for so long that many things are impossible and it’s not. There are lots of advantages to putting a number on it because for example when organizations have a five-year plan or a seven-year plan, I think it’s important for people to know that they’re working towards something whereas I think perhaps if you didn’t have a date, there wouldn’t be a kind of urgency, you see what I mean?

I mean let’s face it, so many people have said that they would have never thought an African-American would be the president of the United States but of course to most people he’s African not African-American because you know how people are saying, “oh he’s like us, he’s one of us” kind of thing. I think I recognize the need for them to put a date on it and I recognize the need for people to have effective planning to say “This is our goal; this is what we’re going to do in year one, this is what we’re going to do in year two” because I think we need that kind of urgency to say “enough is enough”. You know, by 2005 we want to be here, by 2010 we want to be here, by 2015 this is what we want to accomplish. I think that these are areas in which those [goals] are necessary.

How do you go about doing that though? How do you change the attitudes that people have had engrained in their heads for so many years?

You change your way of saying change. You don’t say “change”; you say “grow” because people don’t want to change. Most people that you know, men, women, lovers, boyfriends, friends, mothers, fathers, uncles, everyone has to change. We only allow change in a political sense when we say we need to work towards equitable change or social change but when you’re talking to people on a day-to-day basis; they don’t want to know that you think you need to change them.

I think if we recognize that we grow, that we are all still learning – I say this all the time, I learn from younger people more than I learn from my own age category. I think that if we recognize that learning and education and growth are crucial to any form of development and that’s the thing that I was saying.

One day it sort of dawned on me, I was in a workshop and these students were quite comfortable saying that this was the first time they were having a workshop by a black woman and I’m fine with that, I mean, I call myself black but when I asked them, “what makes you white?” they couldn’t answer me, they never thought about it. They were really uncomfortable. “I don’t know; I’d have to think about that.” Because it’s not something most people think about. If they do, it’s with shame or with guilt like they don’t want to be associated with all the negative aspects that my identity has brought them, in other words, issues of racism or colonialism. I said to them, “Nobody would ever suggest that you identify with anything like that.”

It’s like, I sometimes hear horrible things being said about women. I don’t take it personally. I would say something to the person but I know that that is coming from a place where for men to make those kinds of comments, is an indication of their insecurity half the time but in terms of these kinds of issues, when we ask ourselves and sometimes when people are being asked by me, they will tell me afterwards, “y’know, that really threw me off; I wasn’t expecting it,” because I think Canadians have lots of privileges and part of that privilege is almost not having to examine yourselves and not having to examine your own history.

In closing, is there anything else you’d like to add that we haven’t talked about already?

I think the other thing also, that came out in the talk earlier is that we often forget that gender also means men. One of the things I was saying early on in my talk is that we’re living in an era where notions of gender have expanded. There are many parts now, especially in South Africa where people are doing work around transgender, identities that focus on how this is only about women, it’s not. Gender is not only about women, it’s about recognizing that men and women need to look very critically at either how we perpetuate our own impression or ways in which we need to identify strategies to work towards that elimination.

Too often people spend their time with global protestations but there’s no plan of political action, and that’s what we need. We can have as many global protestations as we like. If those global protestations are not accompanied by a plan of political action, they’re lost and this is why I think that 2005 and 2015 mark[s are] so important, not because I think that if we haven’t reached that goal, I’m going to be so disappointed, no, because I think we need to understand the urgency when it comes to oppression in the same way that people are now understanding the urgency when it comes to the environment.

We can’t just accumulate plastic bags and pretend there’s nothing wrong with it. The minute you pick something up, you need to ask, “Where is it going to go?” So I think that the fact that they are developing strategies to look at particular years of this is where we are, this is where we’re going; it’s very important.

Guelph Reads! April 2008

ROB O’FLANAGAN

MERCURY STAFF

GUELPH

Biko, Nolen, Thoreau, Doucet. These authors might change your life, they might not. But all have penned powerful words capable of inspiring social action — and all deserve to be read.

A thoroughly engaging episode of Guelph Reads drew that conclusion Saturday night, as four passionate readers defended books they felt had the power to motivate social engagement.

This year’s contestants championed books not everyone had heard of, but by the end of the two-hour debate most people in the audience of 100-plus at the Guelph Youth Music Centre seemed eager to place all four books on their must-read list.

Author and aspiring politician Tom King championed Clive Doucet’s “Urban Meltdown: Cities, Climate Change and Politics as Usual,” which argues a lack of political will and the relentless push for economic growth are the drivers of climate change.

“We need stories that engage the imagination and rally us to action,” King said, as he made the case that “Urban Meltdown” is one such story.

It is told with a poet’s voice and has an equal blend of cautionary tales and practical solutions, he said, with a capacity to alter our thinking and change how we live.

Steve Biko’s “I Write What I Like” is not a comfortable read, said author and activist Rozena Maart.

As a teenager growing up in South Africa, Maart said, her identity and political consciousness were shaped by Biko’s writings.

Stev Biko’s daring and penetrating essays built the philosophical foundation of the Black Consciousness movement, which ultimately drove the anti-apartheid movement.

He believed the course of history could be changed, and he challenged his readers to self-scrutinize, to bravely reflect on the very nature of their thinking and the language they use, Maart said.

“Can a man like Biko offer you something?” she asked.

“Yes. He can offer you a vision of your life and future.”

Anne-Marie Zajdlik, physician, and founder/director of the Masai Centre in Guelph, chose an equally challenging book to defend. Stephanie Nolen’s bestseller “28: Stories of AIDS in Africa” changed Zajdlik’s life, inspiring her to tap Guelph’s “incredible compassion” to raise funds for HIV/AIDS patients in Africa.

Zajdlik said “28” tells the stories of the heroes who are saving thousands of lives in Africa. It is one of those rare books that can inspire people to do the right thing at the individual level, while motivating them to insist that politicians also do the right thing, she said.

Norm McLeod, chief librarian of the Guelph Public Library, upheld Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” as a “lovely piece of natural history” and a work that inspires the reader to more thoroughly engage with nature. “To hell with the purists,” McLeod said to “Walden” detractors. “I love the book. It’s great escapist literature.”

“I, like most of you, would like to have a road map to guide me through this stage of life,” he said. Thoreau may serve at least as a partial road map, he added. “Read Thoreau. Read it slowly; savour it.”

Moderated by Guelph Mercury managing editor Phil Andrews, the debate gravitated toward a consensus: The world is full of books, some great, some not great, but most having their own special value for the reader. Some will show you the world the way it really is, others will take you away from reality. But from every book there is something to learn, and there is nothing more exciting than learning.

Ajay Heble and his University of Guelph school of English and theatre studies class created Guelph Reads four years ago as a classroom assignment. Heble is pleased to see that it has taken on a life of its own. Activating knowledge and making it relevant in your own community is an essential part of learning, he said.

“This event really encourages a wider sense of literary, the importance of reading and its social impact, and the role that literature can play in social change,” he said.

To hear the debate, listen to CFRU 93.3 FM on May 6 and May 13 from 8 to 9 a.m. The four books are available at The Bookshelf.