Notes on Psychoanalysis

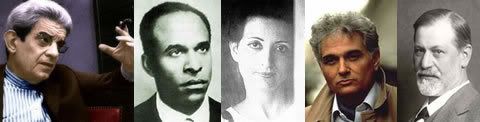

(Jacques Lacan, Frantz Fanon, Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida, Sigmund Freud)

Biographical Information

My work, overall, is influenced by, and contains elements of, psychoanalytic, philosophical and literary discourse. Many literature programmes in Europe insist on psychoanalysis and philosophy as areas of study to complement the study of literature whilst many philosophy programmes teach psychoanalytic texts alongside philosophy ones. I don’t think it is possible for me to do study and teach English Literature and not study psychoanalysis; in the same vein, I encourage students to develop an interest in psychoanalysis if they are studying English Literature and/or Philosophy.

Education and Training

My undergraduate degree is from the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. I took my Masters degree at the University of York, in England and my doctoral degree from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham, England (Literature, Philosophy and Psychoanalysis). When I completed my undergraduate studies I was awarded a social work degree, because social work was my home department—my bursary was awarded through the social work department even though I also took courses in English, Political Sociology and Political Philosophy for several years. The study of social work, under the guidance of Prof. Adam Small, was always philosophy based. I think I studied more of Aristotle with him than anywhere else. Of course, as an adolescent youth of my generation were enormously inspired by Steve Biko. We read Biko’s pamphlets, which were distributed in the province illegally, because his writings were banned, and whatever we could lay our hands on which came from him via SASO, the South African Students Organisation, who later became known as the Black Consciousness Movement of Azania [BCMA]. Anyone who reads the contents of the text now known as I Write What I Like, a collection of papers written by Biko during the emergence of SASO and the BCMA will immediately see the resemblance to Fanon. After my degree I worked at Groote Schuur Hospital where I developed a greater interest in the clinical aspects of therapy and treatment, and later on developed a stronger interest in the work of Frantz Fanon, who was both a psychiatrist and a revolutionary. Anyone who has read Black Skin White Masks, comes face-to-face, almost immediately with his analysis of colonization when he says, “only a psychoanalytic interpretation of the black problem can lay bare the anomalies of effect that are responsible for the structure of the complex.” It was at Groote Schuur hospital where my clinical experience began to take on a greater significance. My Masters thesis is an account of violence against women work in South Africa, leading up to the emergence of Women Against Repression in 1986, the first Black feminist organisation in South Africa. During my Masters degree I developed further intellectual interest in psychoanalysis, reading through rereading Freud and Lacan on their own terms. It was also around this time that I began reading Jacques Derrida and Helene Cixous and began to grapple with their work.

Why psychoanalysis?

I chose to study psychoanalysis to enhance my intellectual knowledge as well as broaden my clinical knowledge. As a child growing up in the 1970s my interest in and engagement with concepts like “consciousness”, “politics” and “mind” became fundamental in how I developed as an adult. It is for these reasons, that their evidence is so strong in my work, and their relationships to the unconscious (disavowal, repression, denial) and language (speech, writing and imagination). Those who read my work see the interconnectness of Biko, Fanon, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, Lacan and Derrida almost immediately, as their influences are woven through my work on Black Consciousness, Feminist Politics, Literature, Philosophy and more specifically my work on Africana Existentialism and Empire and Coloniality.

I don’t think that having a doctorate in any given subject allows one to fully grasp the extent of a subject; it is for this reason that I have continued further studies in psychoanalysis, over the last ten years, at the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research in London, England and have remained active in various organizations and with various scholars doing work in psychoanalysis, sometimes within university settings, other times with respect to cinema. I enjoy taking the knowledge that psychoanalysis offers literary texts and to films especially when teaching various films (see for example my Psychoanalysis and Film page).

What is psychoanalysis?

In a nutshell, psychoanalysis relies on language, mainly speech, as its method of investigation. Psychoanalysis is about understanding the relationship between consciousness and the unconscious. The study of psychoanalysis is in many ways the study of the unconscious, it is never really complete. It is believed that we do not have immediate access to the unconscious––that it is hidden. To be conscious means to be awake and to be aware; it also means to develop a sense of who you are, what your thoughts, aspirations and desires are and how aware you are of their functioning. Freud started the work on the unconsciousness, Lacan took up many of his groundbreaking work on the unconscious; they have each put forward a number of ways in which the mechanisms that keep the unconscious together can be uncovered. If, as Lacan says, the unconscious is structured [in the most radical way] like a language, then it is precisely through language where we can learn to probe, question, interrogate and uncover the processes that hold the unconscious in place. I find Wittgenstein and Derrida’s work in this area enormously insightful.Psychoanalysis is about a questioning; a questioning that takes place through language—speech, the imagination and writing—and this means that every aspect, every process is put through a questioning. Psychoanalysis is also an intellectual field and its body of work provides useful and fruitful conceptual tools for writers, artists and intellectuals who are drawing from their life experience and making connections between their consciousness, their artistic skill, their unconscious, and projecting on a canvas or a page, the extent of what they themselves cannot address, fully, in their day-to-day speech. The conceptual tools which psychoanalysis provide allows many writers, scholars and artists to probe the limits of language: through speech, writing and the imagination, which is often represented in images.

A personal story

In 1973 my family, along with a quarter of a million of District Six residents, were forcibly removed from District Six, our ancestral home. The government had since the 1960s introduced various Acts, one of which was the Forced Removals Act, allowing them to forcibly remove us from District Six– which was slightly outside of the central business district and for which they had other plans. Every year after that on the same day, August 4th, I would break out in hives. For years my friends would joke about how I was trained in psychoanalysis yet could not find a cure to my annual psychosomatic hives. One day, feeling rather restess in Toronto (it was my first year there and I now had to confront many issues in my life) I sat down and wrote a story on District Six, as I remembered it as a child. I was now living outside of South Africa and not sure how to live in a world that seemed so devoid of struggle . . . well as I knew it. Be that as it may, one of my friends used my office for the afternoon; she spotted the story, read it and asked me to kindly give it to her as she wanted to take it to Fireweed for publication. It was published shortly after and I never saw my annual hives again. A year later Fireweed submitted my story to McClelland and Stewart as one of their best, to be judged along with hundreds of others by a blind jury. In 1992, “No Rosa, No District Six,” won “The Journey Prize: Best Short Fiction in Canada, 1992. These days I teach a number of different writing workshops and creative writing courses; I often share this story with students. One of my favourite writing workshops is titled, “Writing Memory, Writing the Body.” I urge students to keep a journal. Writing has a way of bringing consciousness to its brink; visibilising memories, transferring mental images to the page. Many choose to rewrite some of the events in their lives; others choose a path where upon they build on these memories because they provide gateways to consciousness and the unconscious.