In Cape Town’s District 6, despite the brutality of apartheid laws, the lives of people go on. In these five connected stories, the central character is a precocious little girl called Rosa. Through her adventures in the neighbourhood we come to meet and know District Six and its many colourful inhabitants–including Mamma Zila, Auntie Flowers, Mrs Hood and Uncle Peter–and their confusing, enigmatic lives, and all too human quirks.

“A writer in a midst with radical style and uncommon courage. The ability to engage her reader passionately in her narrator’s experiences . . . makes Maart a writer to watch”–The Ottawa Citizen

“Eye-opening, passionate. Maart observes the human costs of apartheid with a keen eye.” –Globe and Mail “

Maart writes with self-assuredness. [A] . . . competent and trustworthy writer.” —Books in Canada

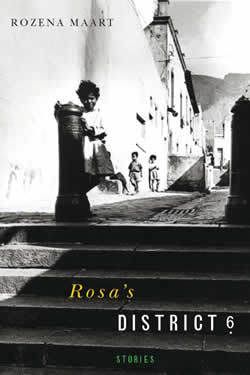

Rosa’s District Six was published by TSAR Publishers in Canada 2004 and New Africa Books, David Philip Publishers, in South Africa, 2006.

Launch event in Cape Town (April-June 2006)

Ribane Nikedi, Fred Khumalo, Rozena Maart–HOMEBRU selected writers

at FM Radio and Exclusive Books joint readings, Waterfront, Cape Town,

with Saxophonist in the background.

Synopsis

Rosa’s District 6 is composed of five short stories. The setting is District 6, in the heart of Cape Town, South Africa, and the year is 1970. The stories are framed around April and May, the autumn period for the Southern Hemisphere, the period where change is pending. In 1970 the Group Areas Act was already in place and the Forced Removal’s Act had already been passed. Parents and grandparents did not tell their children that they were going to be forcibly removed; they did not want to rob them of their joy. From the first story, where a young girl hides in the house of her neighbour, only to discover the untold libidinal pleasures of two women, to a chair which has its own history because a woman decides that it should continue to have its place in her house and fights fiercely to get it back after her daughters take it to be repaired; to a young woman whose mental state has allowed her mother to take ownership of her life, prohibiting her from intimacy with her childhood sweetheart, to a young mother whose husband is on Robben Island, and has to face the moral implications of all of her actions, to the uppity group of people who live at the top of District Six, removed yet part of the fabric of a culture which draws them in, even if it is through a bracelet—these are the ways in which the social fabric of this collection is woven. Sexuality, spirituality, murder, death, madness and ancestral secrets are all delved in, passionately, in suffering and in glory, plunging and splashing from the sea to the heels of those who walk the streets of District6. Rosa, the young eight year old, takes readers on a journey through every little corner of District 6. The collection is composed of five short stories. They are, as follows:

1. No Rosa, No District Six

The young Rosa, aged 8, plays hooky and hides in the house of one of her neighbours. Under the bed, in silent repose, she discovers that erotic love is what binds two women who everyone in her community thought were cousins.

2. The Green Chair

Two teenaged sisters, Jasmin and Latiefa, are left to clean the house while their mother and grandmother go into town to do the shopping. As they clean the house, and a young visitor like Rosa stops by, they dance, frolic and have fun and decide to reupholster their mother’s favourite chair. Refusing to listen to Rosa’s stories and her warning about the significance of the chair, they take it to Caledon Street for repairs only to discover the extent of their mother’s fury and the secret she has kept from them for years.

3. Money for your Madness

Louisa had a nervous breakdown more than 15 years ago but her mother, Nana, a former singer and actress, now lives off her money and denies her a life, including a love-life. Nana, gives her yellow bird all her love while Louisa is denied a life outside of her mother’s house, among the District Six residents. Louisa’s grandmother, Mrs. Naidoo, is ill and cannot help her granddaughter cope with the demands her mother places upon her. One day, Louisa, with the help of Rosa, realises that she has to stand up to her mother, and have a life of her own.

4. Ai, Gadija

Gadija, a dark, beautiful woman, in her late twenties, has twin girls, aged 8 years, from her husband Abdul who is serving time on Robben Island. She, along with her two daughters live with her mother, her two sisters and her brother. Her daughters are friends with Rosa, which means that Rosa’s family and extended family make their appearance here too and certainly make their presence felt. Gadija’s husband is on Robben Island and she now studies part-time at night and works in a fancy department store during the day. Ganief, her childhood friend also studies at the same university. This Muslim woman has to face the reality of living without her husband, her desire for another man and the life she becomes embroiled in as a consequence of the complexities of transgender issues in her family, along with violence, deceit, rape, and finally, murder.

5. The Bracelet

The Uppersiders, those more economically fortunate in District Six, also have their stories: denial and silence come face-to-face with the residents of District Six. Caroline and Nathaniel, an educated couple with an eight year old, Victoria, who considers Rosa a close friend, was assisted by Rosa’s family a few years ago. Each year the two families get together for dinner but this year, Victoria’s father, discovers that his love for a man, a “moffie,” brings him closer to other unspoken truths; he has to face them, much against the harsh words of his wife who threatens that she will reveal his secret. Nathaniel refuses to live in fear of discovery and arranges for his lover to accompany him to meet his parents. In the process, he discovers their secrets and his own untold history, in ways he himself cannot quite handle.

PUBLICIST INFORMATION

Book your reading, lecture or speaking engagement now.

Contact the publicist Ayesha George

You may also contact Rozena Maart

Below is an excerpt from Rosa‘s District 6

1. No Rosa, No District Six

Mummy and Mamma orways say dat I make tings up and dat I have a lively e mag e nation and dat I’m like der people in der olden days dat jus used to tell stories about udder people before dem das why mummy and mamma orways tear my papers up and trow it away but tis not tru I never make tings up I orways tell mamma what happened and mamma doan believe me and I tell mummy and mummy doan believe me too and den I write it on a piece of paper or on der wall or behind Ospavat building or in der sand at der park and Mr. Franks at school he doan believe me too cos he says dat I orways make trouble wi der teachers and I talk too much and I jump too much and I laugh too much and I doan sit still too much and I orways have bubble gum and I orways have pieces of tings and papers and my hair orways comes loose and mamma toal Mr. Franks dat I’m under der doctor and dat I get pills cos I’m hyper active like mamma say “someone who is restless all der time” but Mr. Franks doan believe dat I’m under der doctor cos I make too much movements and today Mr. Henson gave me four cuts cos he say dat I was dis o be dient and dat I cause trouble in der class but tis not true cos you see last week we celebrated Van Riebeeck’s day on der sixt of April wit der flag and we sing “uit die blou van onse hemel” on der grass for der assembly and four weeks ago Mr. Henson teached us Van Riebeeck made Cape Town and built a fort and erecticated a half way station for food and surplies for der Dutch people and der European people so dat dey could rest at der Cape after a long journey and den Mr. Henson also toal us dat Van Riebeeck’s wife was Maria de la Quelerie, dis is true I dirint make dis up like mummy and mamma orways say I make tings up and den Mari der big girl in my class she has her periods oready she toal us she wondered where Maria put her cotton clot wi blood on it in der ship from Holland cos Mari’s mummy told her not to tell her daddy her broder or her uncles about her periods cos men mus never see or know dees tings and den we all laughed cos Mari’s very funny and today we had to give in our assignments on Van Riebeeck and Mr. Henson ga me four cuts on my hand cos I drew a picture of Maria and not Jan and Mr. Henson say dat der assignment was about Van Riebeeck and not Maria and I say is der same ting cos it was part of der same history lesson and Mr. Henson screamed at me to shut up and his veins was standing out and he say dat I was not paying attention and dat he is going to write another letter to mummy about my bee haviour and I ask Mr. Henson if Maria and Jan had children and Mr. Henson say dat I want to play housey-housey all der time and not learn history and I say dat if Maria was Jan’s wife den dey must have had children and den Mr. Henson took me down to der office to Mr. Franks cos Mr. Franks is der principal and Mr. Henson tell Mr. Franks dat I was causing trouble and Mr. Franks believe Mr. Henson and tells me dat I know I should not have been in school in der first place and dat I’ve made trouble since Sub A cos when I was in Sub A Mr. Franks found out dat I was 5 and not 6 and Mr. Franks sent me home and der next day mummy went to school and made a big performance and Mr. Franks took me back cos mamma doan wanna look after me der whole day and cos I start to write when I was four and mamma say I make too much mess on der walls and on der tings and now der school doan want me back no more and Mr. Franks say dat I mus bring mummy to school but I dirint do anything wrong all I wannit to know was if Maria and Jan had children, dat’s all

9 April, 1970

A warm April afternoon greeted the child standing with both arms on her hips. Her sticky fingers cupped the flesh around her cheeks as she eagerly observed the friendly wall upon which her writing spoke her truths. Her eyes, notable for observing several activities at the same time, moved over the written area, sealing it with a narrowed look of approval while her mouth pouted in a somewhat revolutionary way. Rosa took the sides of her dress and tucked them into her bloomers. It bubbled like a fluffy pancake as the Cape Town afternoon wind encircled her body; her brown cinnamon legs sweetened its appearance whilst also holding her rebellious posture together. She giggled as she saw her reflection in the sun. Rosa lifted her school-case and threw it across the gravel park. The stones were filing her case smoother and her shoes now had to suffer the grinding the brick walls were to put them through. The crevices between the stone bricks of George Golding Primary School knew Rosa well. She climbed with no difficulty. Once at the top she leapt like a grasshopper and knelt on the ground for a while pretending to sort out pebbles. Rosa undid her buckled black shoes and knelt forward to pick the thorns off her socks, throwing them one at a time at the row of marching ants. She removed the pieces of her dress still caught between her bloomers. Her plaited hair, tentacled in spiderly fashion, lay scrunched up between her legs. Its web of discomfort awaited the mystery that only Rosa could decide. The black balls of her eyes surveyed the area and alerted her to her peers some yards away. It was nobody she knew and no one who would complain to Mamma Zila. Upon deciding whether to go home through Hanover Street or down Constitution, Rosa chose Hanover. Verbalizing her decision to herself, she exclaimed, “In Hanover Street there are lots of busy people and nobody watches your feet, only your face!”

The shuffling of feet, the racing of pulses, the screams of little children being bathed by older sisters and brothers in the backyard, the green hose pipe curling itself up among the plants, the sound of several liters of urine being flushed down the toilet in the backyard, where its circular swashing motion competed with bundles of early morning hair awaiting its disposal, the sound of creaking floors as boys and men raised themselves from their place of sleep, the smell of fire as the stove brewed its first round of morning tea, the ravenous chirps of gulls circling the street for morning bread crumbs, the sound of peanut butter jars being emptied by eager hands clenching sharp knives, the smell of fresh tobacco as working women and men light their first weed, the aroma of freshly braised turmeric onions from homes already preparing the base for tonight’s supper, the ripeness of tomatoes, onions, potatoes, Durban bananas, and Constantia grapes shining like jewels in Auntie Tiefa’s cart, the disgruntled noises of dockyard men walking the charcoaled streets, their feet removing chips of wood and cigarette butts from the previous night’s fire, their eyes looking ahead matching their place of work-the sea, with the sky above their heads-and spotless Table Mountain–gray with not a speckle of white on its top–these formed the backdrop of this early morning Cape Town experience.

Rosa was searching for a place to hide until the streets were clear. She “morning Auntied” everyone in sight as women took their children across the street and set them on their way to school with older children from the neighbourhood and others carried their day’s produce, bundled on their heads or packed in their carts for purchase, to Hanover Street. There was a regional meeting for teachers at George Golding Primary School and Mr. Henson, Rosa’s class teacher, was not attending the meeting and would be supervising their class the whole day. Mr. Henson and Rosa had a history of conflict, where the former had asked for Rosa to be expelled from school. The female-child recollected her thoughts and smiled to herself, remembering how Mamma Zila, Rosa’s maternal grandmother, had asked politely that Rosa be readmitted. Mr. Henson, being a rather stern man who, on many occasions, demanded far too much respect than Mamma Zila thought he deserved, asked that Mamma Zila sign a written document for Rosa’s conditional re-acceptance and, in addition, state that Rosa was to behave and do as she was told. Resenting his authoritarian tone, Mamma Zila held Mr. Henson at the collar, lifted him out of his shoes, and insisted that Rosa be readmitted without conditions, mentioned a few of her relatives’ names–suggesting a larger, family gang fight–and upon stating these, Rosa was re-accepted. Mr. Franks, the principal, warned that if Rosa was found doing anything unlawful, like writing on walls, engraving graffiti on wooden desks, influencing other female-children, or throwing stones, she would be expelled permanently.

Deciding where to run and hide was not very difficult at 7.30 in the morning. The men from Ospavat factory were all outside waiting for the two sirens before the start of their working day: the wooden chips on their overalls still visible from the previous day’s work. The women one usually saw at 7.45 rushing towards the red-faced Mr. Stowe waving their sandwiches to their white doorman and supervisor. For many of the men, it was their first opportunity to look between their prepared sandwiches and bargain with Auntie Tiefa for some tomatoes or maybe some homemade mango pickle. “Don’t kick the bloody tins. You two boys better start walking before I come down with my stick. I mean right now you two devils.” Motchie Tiema shouted at Wasfi and Ludwi to go to school. “Morning Motchie, the children being troublesome again,” three men shouted. “Ai tog, you know when these boys start to grow hair on their balls.” The men all laughed, shaking their heads in agreement and for fear of not wanting to disagree with Motchie Tiema. “See you men later, the beds are waiting for me.” “Salaam Motchie,” Auntie Tiefa greeted. “A leikom Salaam Tiefa. I’ll give in my order on Thursday, the usual you know. Send Krislaam to Galiema from the Seven Steps”. “Okay Motchie,” replied Auntie Tiefa. The two women waved good-bye. Auntie Tiefa loaded the cart for the day’s sales of fruit and vegetables. A few men gathered round to buy some fruit before Auntie Tiefa took off to Hanover Street. She hit their hands away and made sure that nobody was helping her load or themselves with fruit. “No focking hand-outs for anyborry, I dirint ask you to help, okay.” Some of the men grumbled a bit and reluctantly they moved away. “Are you talking to me or chewing a brick Boetatjie? Your father went with my father to the war, so don’t try your kak here,” Auntie Tiefa reprimanded the man. “No, no, no, Auntie T, it’s time to leave now and the siren is going off any minute and I jus wannit to save you der trouble.” “Gmmm! Okay take der tomato and skoot.” And so they did. The men were pleased when the first siren rang and they could move towards the big white building. Children walking past the factory automatically kept their ears closed; others yawned the full duration of the siren–some exercising their jaws, others competing with the loud factory sound.

Rosa, hiding in the lane, pretending to fasten the buckle on her shoe saw the opportunity to run. Rosa noticed a moving vehicle. It was the Free Dispensary van which came to collect Uncle Tuckie. Mrs. Hood and Auntie Flowers were standing at the door waiting for the driver to come to a halt and open the van. Both the women lifted Uncle Tuckie into the van, dragging his lame legs one at a time. Rosa noticed that the two women were dressed like they were going visiting or shopping. Mrs. Hood was not wearing her apron and Auntie Flowers wore her stockings. The elastic garters were visible to Rosa as she watched Auntie Flowers bend to lift Uncle Tuckie’s legs. Hiding inside their house would be a wonderful idea, she thought. She could always leave and since nobody locked their doors anyway, it would be as easy as chewing bubble gum. Rosa removed her shoes, held them in one hand, and entered the home of Mrs. Hood without the two women noticing. The second siren rang at 7.45 a.m. Now everybody would be inside attending to household chores. Auntie Raya was late, so was Mrs. Benjamin. Both women were shouting at Mr. Stowe to wait for them. “Meneer, we’re coming now-now . . . . Meneer.” Mr. Stowe smirked in his usual arrogant manner. Auntie Raya folded her apron and tucked it under her armpit, nodding thankfully to Mr. Stowe for waiting on them. “Ai, Tuckie was really a handful dis morning, der man jus doan stop talking about der war.” Mrs. Hood stooped to pick up Uncle Tuckie’s plastic gun and shook her head, still communicating to Auntie Flowers.

Rosa heard the two women coming into the house. She was at a loss for where to run to now. She ran into Mrs. Hood’s bedroom. Both women were approaching the kitchen, or maybe the bedroom. This she was not sure of as both rooms were close to one another. Rosa slipped under the bed. “Ai no! Mrs. Hood dirint take the pee-pot out yet,” Rosa sighed, and cursed the sight of the urine-filled pot sitting boldly beside her. The female-child fitted her shoes like gloves into her hands and placed them, rubber facing downward, onto the floor. She soon realized that she would be needing both hands for protection. She wiggled them out slowly and stuffed the shoes in her unbuttoned bosom, placed both hands over her mouth like a mask and stared at the two pints of urine in the cast iron pot. She lay virtually immobile. When she lifted her head the diamond pattern wire from the bed caught her hair. When she tried to wiggle to each of her sides, the shoes, boxes, and other stacked away household goods prevented her from moving in the limited space. Auntie Flowers always dragged her feet and when Rosa could not hear them any longer she knew Auntie Flowers was standing still. Auntie Flowers placed herself on the unmade bed, right in the middle of it. Rosa’s inquisitive face fitted neatly between the grown woman’s legs. Auntie Flowers raised herself from the bed and walked towards the mirror. The springs above Rosa’s head gave a bowful bounce, a salute which seemed appropriate since Uncle Tuckie’s military boots seemed to ask for one. The urine pot got the stares from

Rosa. Rosa’s attention was soon fixed on Auntie Flowers who slowly removed the pins from her circular bound hair. Rosa had never seen Auntie Flowers with her hair down. Although Auntie Flowers was quite fond of her, now was not a good time to talk about Auntie Flowers’ many hair pins. The child was silent.

She was mesmerized by the sequence of events, most of which she would never have observed had she not sought the privacy of a small space under Mrs. Hood’s bed. Rosa’s mouth fell open as she counted, “Aaah…15…16…17…18…” Tasting the urine stench against her palate, she closed her mouth instantly, placing both her hands over her tight-lipped mouth. She continued counting by nodding and memorizing so that she could remember to tell Nita and maybe write it on one of her favourite walls. Auntie Flowers started singing, “Wait by the river, wait by my side,” as she brushed in long, silent strokes. She sang in a funeral voice, Rosa thought, the kind of voice that vibrates, makes waves, and causes for everyone to cry. Auntie Flowers’ voice was deep and passionate. “Wait till the moon is right, wait up all night, wait till it’s morning, come hold me tight, wait till we kiss good-night, come let’s not fight.” Opening and closing her mouth was more agonizing than Rosa had anticipated. She wished she had told Mamma Zila that she was ill and could stay home to watch Auntie Flowers under better conditions. The urine lay still in its place. Glancing at it reminded Rosa of how her excitement was hampered by its presence. Rosa watched carefully as Mrs. Hood brought the metal bath into the bedroom. Mrs. Hood moved towards Auntie Flowers and stroked the woman’s hair. It was not so unusual for Rosa to see Mrs. Hood plant a kiss on Auntie Flowers’ cheeks.

(Refer to the book for further reading).